The COVID-19 quarantine has been challenging to the world of movies. Film distributors have relied on home streaming, with mixed results, while a new wave of pop-up drive-in theaters has gained traction (South Jersey, where the drive-in theater was invented in 1933, is fortunate to have the last remaining one in the state, The Delsea Drive-In in Vineland, which has recently resumed operation).

The COVID-19 quarantine has been challenging to the world of movies. Film distributors have relied on home streaming, with mixed results, while a new wave of pop-up drive-in theaters has gained traction (South Jersey, where the drive-in theater was invented in 1933, is fortunate to have the last remaining one in the state, The Delsea Drive-In in Vineland, which has recently resumed operation).

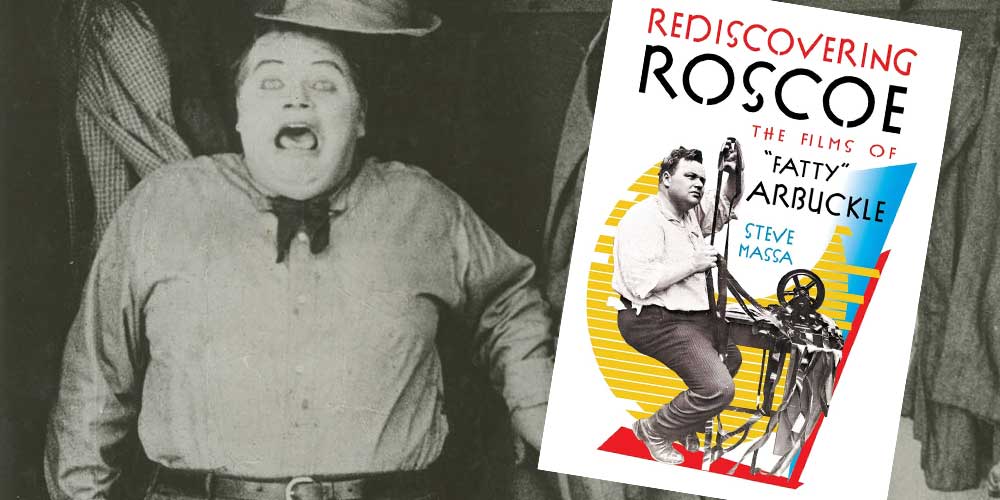

The world of silent film has been an inspiration during this time. With film scorer/programmer Ben Model, author Steve Massa has participated in Silent Comedy Watch Parties, which have brought the community together while extending its fanbase, to all ages. A productive member of the community, Massa has recently released a much-needed book on the important but oddly neglected silent star Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle from BearManor Media Publishers. An independent publisher focusing on all aspects of film history, BearManor is familiar with such territory, having published a text on another largely forgotten silent star, Ben Turpin, in 2015. The press has recently reached the top of Amazon.com’s performing arts reference list with 1000 Women of Horror: 1895-2018 by Australian critic/programmer Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, who regularly contributes probing DVD commentaries.

Film historian Massa has sifted through a sizable amount of research to uncovered details of an extensive filmography, consisting of, at times, several films made per month. With this text, silent film fans now know what to seek out, while we can learn about what has been lost over time, like much of the body of silent-era cinema. Massa includes copious photos from Arbuckle’s career, which was sadly cut short in 1921 by a scandal involving the death of young actress Virginia Rapp. After directing under a pseudonym, he had a brief comeback before passing away in 1933 at age 46.

Before Massa’s book arrived to me in the mail, I was expecting a slimmer text, like the satisfying encyclopedias on Lon Chaney by Michael Blake and Film Serials by Geoff Mayer. True to its subject’s delightful form, Massa’s is a hefty doorstopper of a book.

I caught up with Massa over email to discuss his new book, the legacy of Arbuckle, and the world of silent film today.

I’d like to hear about your first experience viewing a silent film, and the first time you encountered a Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle movie.

My first experience with a silent film was in 1959 when I was four years old. It was at an end-of-the-year festival at the elementary school where my aunt worked. Besides hotdogs and booths with prizes, cartoons were shown in the auditorium. After a couple of Woody Woodpecker cartoons a one-reeler came on about a little guy with a mustache trying to park his car and the cop who was lying in wait to give him a ticket. No matter what machinations the little fellow went through the cop was always there with ticket ready. Although I can still hear our laughter echoing in the auditorium, I’ve never seen that short again nor been able to identify what it was.

It wasn’t long after this that I discovered silent comedies on television and became completely hooked. These were programs such as Who’s the Funnyman? and Comedy Capers, where silent comedies were edited down, topped off with “funny” narration and music, and repackaged for kids. This was my initial exposure to comics like Harry Langdon, Billy Bevan, the Smith Family, A Ton of Fun, and others. While there was no information given on any of the performers or films, I began recognizing faces and routines. At the same time I was getting a steady diet of Laurel & Hardy, The Three Stooges and The Little Rascals sound shorts, where I spotted many of the same silent performers.

Probably due to the fallout from his scandal there weren’t any Arbuckle comedies included in these series, and they generally weren’t around. I was a teenager when I saw my first Arbuckle short – Blackhawk Film’s release of Fatty’s Magic Pants (1914) – which really didn’t make much of an impression on me. My first real look at Roscoe didn’t come until 1983 when film historian William K. Everson programmed an all-Arbuckle evening at New York’s Collective for Living Cinema. Professor Everson showed The Waiter’s Ball (1916), the feature Leap Year (1922), and his comeback sound short Buzzin’ Around (1933). This was an eye-opening experience, and I became a fan, looking for more of his films wherever I could find them.

I imagine that this project took some time, considering the length of your text, though it’s very approachable. How did you know when you were satisfied with the manuscript?

I seriously started gathering research for the book in 2006, the year that Ron Magliozzi, Ben Model and I mounted an Arbuckle retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. It wasn’t until about three years ago, when I finished my previous book Slapstick Divas: The Women of Silent Comedy that I decided it was time for Roscoe. I had a good deal of research ready by then, had seen more films, plus had made many notes over the years, so I put it all together and started working.

I had never written a “films of” book before, and besides entries for each individual film I needed to create descriptions of, and transitions to, the different phases of Roscoe’s career and life. Once those were all done I added two appendices – one about how the films survived and where to see them today, and the second on the other “large” silent comedians that came before and after Arbuckle.

How important is the silent film community to your work? I see much evidence in your book, from the contribution by accompanist/programmer Ben Model and others.

Oh, being a part of the silent film community is extremely important in doing a book like this. Such a wide variety of materials is needed – images, information, access to films – there’s no one-stop shop. Having been programming and involved in silent comedy shows for thirty years I have a great group of colleagues who are very generous, who go out of their way to share what they or their archives have, and are ready to brainstorm and suggest other sources (you can’t go wrong with input from someone like Kevin Brownlow). It’s a very passionate group of experts who help each other out, as the common over-all goal is to showcase the films and get the word out on them.

I see Arbuckle as a uniquely physical performer, one who had the kind of power we see in Keaton but seemingly with more energy. So many, though, love the grace of figures like Chaplin – what else do you see that Arbuckle adds in this regard?

Roscoe had a good deal of the same physical grace as Chaplin – which is a startling contrast to his large size. He was incredibly light and fast on his feet, and took an endless variety of tremendous falls. There is also his amazing dexterity with props – where he flips pancakes and catches them behind his back, tosses knives in the air to have them land where he wants point down, and hurls other projectiles (sometimes pies) with deadly accuracy. Like the other truly great physical comedians – Keaton, Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Laurel & Hardy, W.C. Fields – he had a pronounced capacity for hard work (which you don’t see on screen but makes what they do look so easy), and an immense focus that gave a cleanness and precision to all his physical business.

Naturally, you address Arbuckle’s scandal, which sadly halted his career. How important of a motivation was this to your project? I’m sure his work in the early sound era of cinema, as a director – after his scandal and largely overlooked – was an important drive for your writing.

The scandal really halted his career only temporarily, for about a year from the end of 1921 to the end of 1922, after which he went back to work behind the scenes and was very busy until his death in 1933. Almost all of the previous books have focused on the scandal and trials – treating his career and work before as just a lead-in to the main event, and then his post-trial life as barely an afterthought. The scandal created a taint that kept his films and his innovative work as a comedy creator from being properly regarded and examined.

When silent comedy and people like Keaton were being rediscovered in the 1950s and 1960s, Roscoe’s films were still languishing and rarely revived. My motivation was to explore his work, as a writer/director as well as a performer, and see how it holds up today and compares with that of his contemporaries. Luckily a fairly large amount of his films survive – silent and sound – with outstanding example like Fatty and Mabel Adrift, His Wife’s Mistake (both 1916), The Butcher Boy (1917), The Iron Mule, Curses (both 1925), Honeymoon Trio (1931), Bridge Wives (1932), and Buzzin’ Around (1933) available and able to speak for themselves.

Which authors of film do your turn to for inspiration? Are there any writing on film outside silents that are important to you, or criticism on the other arts?

Authors who have influenced me are Kevin Brownlow, William K. Everson, Leonard Maltin, Sam Gill, Kalton C. Lahue, Richard W. Bann, Brent Walker, Rob Stone and Randy Skretvedt. I like a no-frills style that really focuses on the subject from a historical point of view. I hate academic and theoretical film books, where it takes twelve pages and copious footnotes to describe the relevance and implications of a gag or comic moment that takes only ten seconds to watch. I’ve tried to read them but my eyes roll back into my head and I’m temporarily blinded until I finally put down the book. Silent comedies, above all, are fun, so I think writings about them should be fun too. I try to keep things loose, incorporate humor, and avoid being dry and boring. I go out of my way to not be academic – I purposely don’t use footnotes, and try to be as conversational as possible. I also always try to find and use quotes from my subjects, as I think it’s important to try and give a suggestion of their own voice. I hope I’m successful in keeping things fun – most of the feedback I get on the books leads me to think I am.

How extensive was the archival research for this book? And in your perspective, how much background should the casual silent film buff have on a star or prominent figure?

The archival research for Roscoe was extremely extensive. I work at a major arts archive, the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, so much of my research always starts there with our amazing collection of clipping files, motion picture trade journals, photographs and other ephemera. The Museum of Modern Art, Library of Congress, George Eastman Museum, the Academy’s Margaret Herrick Library, EYE Filmmuseum, Netherlands, the Cineteca di Bolgna, and the Royal Belgian Cimematheque were the other major archives visited or where info and materials like films and images were accessed. Again private collectors are an important source, and now an amazing amount of research can be done from home with the Media History Digital Library’s Lantern Search.

As far as how much background should the casual silent film buff have on a star or prominent figure – I don’t think they need much of any really to enjoy the films. The nature of silent comedy is whether you find what you see funny or not. The viewer doesn’t need to know anything about Charlie Chaplin’s music hall background or the years that W.C. Fields spent perfecting his juggling or pool table routine to find their screen antics funny. All that matters is that it makes them laugh. It’s true that when most people find a performer that they love and find funny they then generally want to know all about them.

How is it to publish on silent film these days? I’m curious about how you found your current publisher, and your other experiences.

Well, writing about silent comedy is certainly a niche endeavor, so luckily I’ve never done it to make a profit. It grew out of, and goes hand in hand with, my film programming and presentations. Although since I started publishing my speaking fees and programming honorariums took a jump up. I started out writing notes for screenings and festivals that I was doing, and then it progressed to articles for film journals like Griffithiana.

As far as starting to write for BearManor Media, in 2010 I contacted publisher Ben Ohmart about doing a potential collection of my essays on silent comedy. He liked the idea, and that became my first book Lame Brains and Lunatics: The Good, The Bad and The Forgotten of Silent Comedy. Since then we’ve done Slapstick Divas: The Women of Silent Comedy, and now Rediscovering Roscoe. I’ve also been involved with Ben Model on silent comedy DVDs that are funded with Kickstarter campaigns. Often we’ve gone way over our original monetary goal, so as extras Ben has published and I’ve written booklets such as The Mishaps of Musty Suffer and Marcel Perez: The International Mirth-Maker.

Film notes are fun to write, and I continue to do them for the screenings we do at our Silent Clowns Film Series and elsewhere, as well as for organizations like the National Film Preservation Foundation and the Criterion Collection.

I wonder how many silent film buffs are reading in-depth on silent film stars? I’d imagine it’s a higher number than other fan bases, though there are a variety of writing styles and purposes.

Silent film buffs are a very passionate group, and I think devoted to reading in-depth on their favorite stars or directors. This is indicated by the number of very substantial and detailed biographies that have come out in just the past few years on people such as Michael Curtiz, Douglas Fairbanks, William Fox, Clarence Brown, Mabel Normand, and William Cameron Menzies. There have always been new books on Chaplin and Keaton, but the output has widened to include artists who have been overlooked or often taken for granted.

With the current crisis of theatergoing due to COVID-19, I’m sure silent film programming is especially affected. What measures are being taking in the community? I see that you have been involved in Silent Comedy Watch Parties, hosted by Ben Model, which is a wonderful concept.

Yes, with the current pandemic silent film programming, any kind of public film programming, has ground to a halt. Screenings and films festivals have been cancelled, or at best postponed until around November (when I think there may be a huge glut of film festivals). Thanks to the internet film archives and other organizations have been reaching out by streaming some of their holdings. This has created something of a lifeline and important diversion for silent film fans. Ben Model and I had a lot of screenings and events cancelled. Since our audiences couldn’t come to us we decided to do a weekly free Silent Comedy Watch Party and bring an hour’s worth of silent comedy to them. This is an idea that Ben had had for a while, and this seemed like the perfect time to try it out. We wanted to stress the live event element, that everyone tunes in in real time, but the response has been so tremendous, and viewed around the world at various times, that we decided to archive them and have them available so people can watch them whenever. It’s very informal – Ben plays for each film, and we give background info – so it’s kind of a way to invite people to a home screening and have some fun during these difficult times.

I know that some people involved in film programming are worried that these online streamings will have an adverse effect on public presentations when things resume, but I don’t think that’s the case. I think the desire for the public screenings will be stronger as an amazing number of people are being exposed to this type of films for the first time. That’s what Ben and I are hearing in the responses we’re getting from around the globe – Argentina, Brazil, Ireland, everywhere. Even more important is that people are watching with their children – we’re getting feedback from parents, and the kids themselves, telling us how much they love the films and want to see more. Kids and young people (under forty) are the target group that we’ve been trying to reach with our Silent Clowns Film Series because without them interest in silent films will eventually die out. Strangely, because of COVID-19 we’ve been able to tap into this new audience and turn them on to silents – definitely a situation of taking lemons and making lemonade.

Which Arbuckle would you recommend newbies check out first? I always return to The Knockout (1914), and teach the film in my silent units at Rutgers; the film’s a treat, since we get to see Chaplin at work, too. Or how about a program of shorts, and a rationale?

The film I would recommend people see for their first Arbuckle experience is 1916’s The Waiter’s Ball. It’s the film that Bill Everson showed in 1983 that opened the door for me, and is a quintessential distillation of everything that Roscoe could do in front of, and behind, the camera. Others that are very good for a first look are That Little Band of Gold, Fatty’s Tintype Tangle (both 1915), Fatty and Mabel Adrift (1916), and The Butcher Boy (1917). I think the ideal program is still the one that Everson put together – The Waiter’s Ball, the feature Leap Year (1921), and his sound comeback short Buzzin’ Around (1933) which takes an audience from his first full flowering to his last hurrah.

Matthew Sorrento teaches film studies at Rutgers University–Camden and is co-editor of the journal Film International (Intellect Publishers; filmint.nu). His current research includes film noir and the Blacklist, Richard Brooks’ The Brothers Karamazov, and David Fincher’s Zodiac.